The tour around Druthal continues, with map and write-up on the eastern neighbor, Kellirac.

—

“Kellirac is not as dangerous as they say. But when I see the bonfires, I make sure my boots are on and my sword is sharp.” –Desenánderez, Acserian missionary

“I’d rather have them as an ally than an enemy. Never make an enemy of people who eat their own dead.” –Darius Estinian, Kieran Senator

“Magic is like flowing water, and in most of the world it is a mighty river, coursing with strength and dependability. In Kellirac, it is a dry creekbed, churning rapids and a waterfall, all at once.” –Xaveem Alassam, Imach Warlock

“You cannot kill the fire. You cannot kill the storm. You cannot even kill my army. The dead never leave us.” –Kellirac Warlord Luten Torgsed

The nation of Kellirac is thought by most other nations to be full of primitive, almost animalistic people. The mere mention of Kellirac bonfires is enough to scare children in Acora and Oblune, and the sight of Kellirac troops on the field of battle can terrify most western armies.

There is talk of wild magic, impossible beasts, cannibalism and even the dead walking and speaking.

This attitude is mostly based on misunderstandings, rumors, and half-truths. The truth is Kellirac has much in common with where Druthal and Waisholm were a few centuries ago. But while Kellirac is harsh and unforgiving, it is more than fierce warriors and terrifying folk customs. Kellirac is a region of rich history.

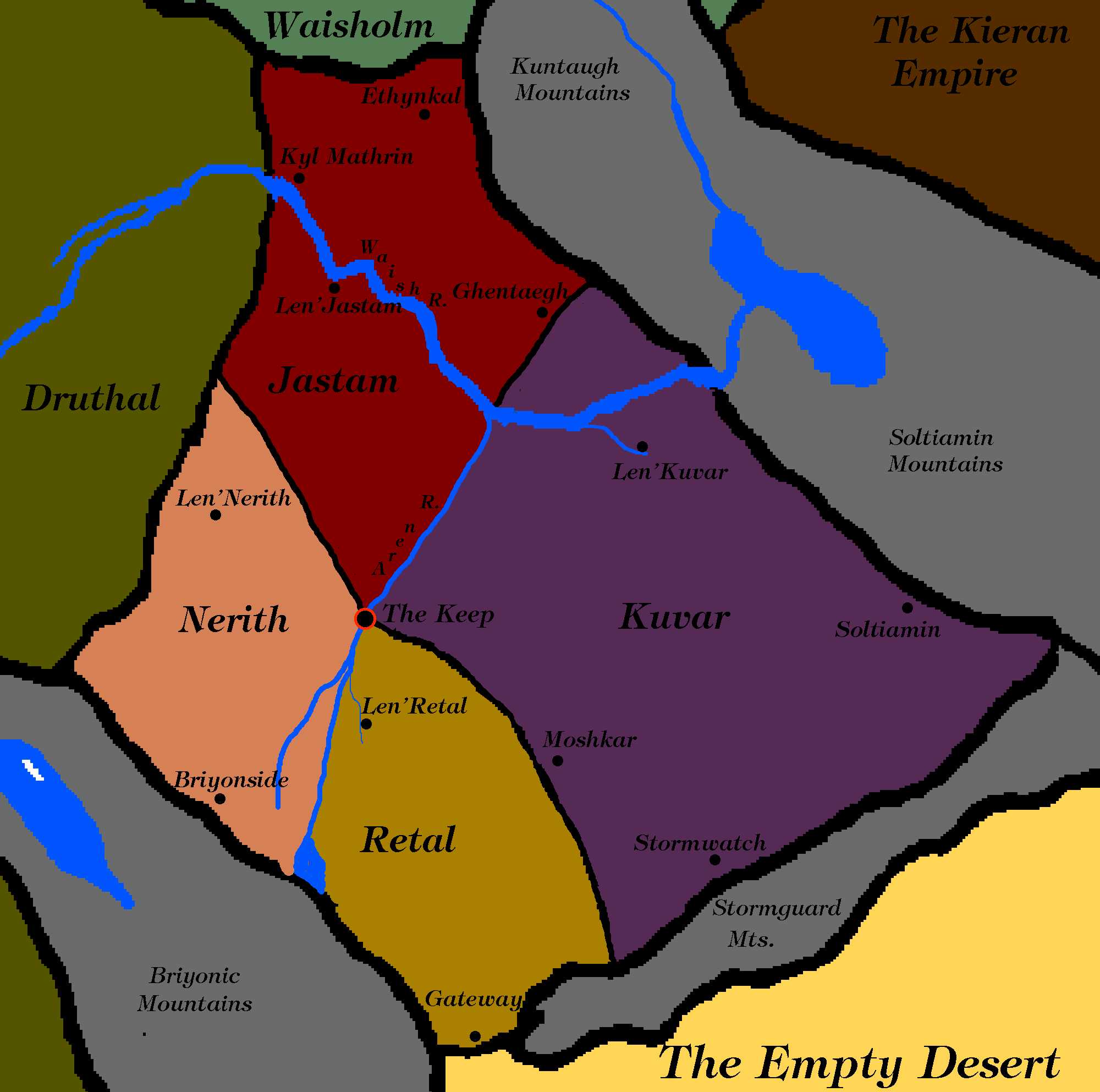

Kellirac is not a unified nation, but four: Jastam, Nerith, Retal, and Kuvar. Over the centuries the Kelliracqui people have repeated the cycle of coming together under a single strong ruler, and then broken back up into the four regions. Each of the four provinces is governed by a feudal Lord, and all four Lords make decisions regarding their region. Any small degree of unity depends on the moods and alliances of the four Lords, but typically they all agree that none of them may take the Unworthy Throne in the Keep. The Keep was originally a fortress built by the Kierans during their occupation of the region. It has stood for centuries, and has become the center of Kellirac political life.

Each local warlord has men (and sometimes women) in his official employ that act as a local law authority. This office is called Meeschun, and enforces the property rights, tax levies, and other decrees of the nobility.

In theory, Kellirac obeys the Kieran legal code that was established during the Empire’s highest days. In reality, crime in Kellirac is handled personally. The wronged party regularly takes revenge as he or she sees fit. “Kellirac Justice” is an often-used phrase to mean bloody revenge.

This leaves the office of the Meeschun with little to do but arrest poachers and collect taxes. However, crime is not much of a problem in Kellirac, as life is too much of a daily struggle to worry about who stole from whom. For many communities, if an entire day has gone by with no injuries, illnesses, or deaths, a celebration is held. In this environment, theft is a rare occurrence. Adding to this fact, there is little to steal, and few well defined laws. As a result, Kellirac tends to have little need for an organized system of punishment.

Criminal activity in Kellirac is an affair best left to those involved. In general, disagreements and disputes are settled simply, either by gathering up one’s brothers to beat the offending party senseless, or asking the Meeschun to deputize the offended party, who then gathers his brothers to beat the offending party senseless. In more extreme cases, the offended party can challenge the other to a duel. Duels in Kellirac are far less formal and ritualized than they are in the rest of the world. They consist of a challenge, two swords, and one person dying.

One tradition that stands in many of the smaller, more remote communities is “Sticking.” Sticking occurs after a crime that offends the sensibilities of the community, such as impregnating a young girl then refusing to marry her. In this punishment, the strongest males in the community form two lines, and each one carries a heavy cudgel. The offender must walk, not run, between these two lines, and each man takes as many hard swings as he wishes at the offender’s head and upper body. If the offender makes it to the end of the line alive, he is forgiven by the community. Few people survive Sticking.

Kellirac does not have a standing army. Instead, the feudal system of responsibility in Kellirac allows a Lord or noble to gather his warriors and vassals at any time. Refusal to serve a noble is considered a crime in some areas, but not in others, and the severity depends on the noble involved. However, few men refuse the call to arms when it has been made.

Desertion, on the other hand, is common. Many men who are conscripted for a prolonged battle fear for the well being of their families, and desert to return home for planting and harvest. This has led to the aphorism “The Kellirac fight with the seasons.” Desertion for reasons of cowardice is punishable by death, but desertion to return for harvest or planting is often forgiven. In one recent engagement on the Druth border, a battle between the Kellirac and the Druth waged for several weeks, but ended abruptly when the early onset of harvest season took the Kellirac by surprise. In the morning, after Druth battle lines had been re-drawn, the Druth cavalry discovered that the Kellirac had gone home, leaving only one small unit behind who delivered the message “We shall come again after harvest.”

The Kellirac armies are considered formidable despite their technological disadvantage, partly as a result of their reputation for savage fearlessness. During the Rebellion, as Kellirac fought on the side of the Empire, many Druth and Waish warriors told stories of atrocities, such as the dismembering of dead enemies to keep as trophies, and the ritual eating of the slain. While cannibalism is a fairly well documented historical practice in specific, ritualized circumstances, there is no proof that cannibalism has been a part of Kellirac military practice since the days of Arengi.

Kellirac soldiers are reckless and wild by the standards of the other Trade Nations. They have few skilled archers, and virtually no cavalry, as there is little call for it in mountainous Kellirac. But what the Kellirac lack in formalized training, they make up for in passion, ferocity, cunning, and reputation. The sight of naked or fur-clad Kellirac, waving axes and picks, shouting bloody war cries as stag horned trumpeters blow horns from the hilltops and javelin wielding troops appear from the hills and melt back into the mists have routed more than one line of Druth cavalry.

Despite their large deposits of precious metals, Kellirac is relatively poor in metals that are useful for weapons and armor. As a result, most Kellirac warriors are equipped with simple leather armor, spears, and wooden shields. Swords are expensive, and are almost exclusively used by knights and lords.

There is no formal system of education in Kellirac. Those young people (men and women) who show intellectual aptitude early are sent to one of the many Acserian missions in the region to study, or on rare occasions sent to Druthal. On the other hand, Kellirac children are taught by their parents to hunt, track, forge, sew, and perform many other tasks necessary for their culture and survival. While Trade is spoken throughout Kellirac, the traditional language of Sechiall (pronounced sake-hi-ell) is spoken by far more people, particularly those in more isolated settings. In fact, given a choice between raising a child to speak Trade or Sechiall, Kellirac mothers will choose Sechiall first. In the eyes of a Kellirac, Trade is a fine language for describing politics and economics, but fails miserably when trying to describe the intricacies of day-to-day life of the Kell character. However, many subtle intricacies of the Kellirac language are lost in translation, making Kelliracs sound stilted and confused when speaking Trade.

Only a small minority of Kelliracs can read the Trade language, and that is mostly restricted to the nobles and richer families.

Although a Trade Nation, Kellirac has poor relations with the other members in general. Kellirac has a long history of attacking Waisholm and Druthal. For the last several decades, relations have been antagonistic, but rarely openly hostile. The Kellirac still harbor bitterness over several crushing defeats at the hands of the Druth and Waish armies.

Many Kellirac have fled their own country, living as wanderers or as an outskirter subculture in Druthal. These Racquin mostly keep to themselves, and hold on to elements of Kell culture and language.

The Kellirac are a superstitious people, and the constant numinic storms and magic flares do nothing to ease these feelings. The Kellirac are very suspicious about magic, and as they see it, its connection to the dead. Many Kellirac consult diviners and necromancers regularly. But as much as the people of Kellirac respect magic, they fear it as well. Kellirac know that magic is a volatile, often unpredictable force, and treat mages with respect, awe, and fear combined. The Kellirac are more likely to practice ritualized magic than any other people are. Bonfires, ritual effigy burning, and (according to Acserian rumor) human sacrifices are part of Kellirac ritual observances, and have developed an unfairly negative reputation among outsiders.

In the minds of most outsiders, particularly the Acserian missionaries, the bonfires and cannibalism are the most frightening and the vilest of Kellirac superstitions. According to Kellirac folklore, some of The Wretched (see below) entice human followers with promises of wealth, power, and glorious battles. Those Kellirac who agree to follow The Wretched set bonfires at the waning Blood Moon, and chant ancient, forbidden death chants. These people then become vessels for The Wretched, who feed on the flesh of the living as a source of their power. After nine nights of bonfires, ritual sex and dancing, and preparations for battle, these groups of Human Wretched will attach the nearest village. Many Kellirac villages have taken to launching surprise raids on the bonfire encampments, as the Human Wretched require the full nine nights in order to fully transform.

The religion is based upon the dead. The goal is to die honorably, and be reunited with one’s ancestors in the next world. Those who die dishonorably, particularly by an act of cowardice in a lost battle, become “The Wretched,” spirits who are tainted, not allowed passage beyond. Those who die in a losing battle but die with honor or those who do not die in battle become The Wanderers, undead spirits who aid humanity in hopes of being allowed to move on.

When Acserianism came to Kellirac, attempts were made to “civilize and educate” the Kellirac. However, the new religion never supplanted the original pagan beliefs. While some Kellirac have become Acserians, most notably Valsam Du Retal, one of the Kellirac Lords, most are either still pagans, or have become part of a splinter faith of Acserianism. This religion, called Samacheriai, is a blend of traditional Kell beliefs and somewhat obscure Acserian beliefs. Samacheriai believes that there is one all-powerful God, and that he sends prophets to the world to help humanity understand his ways. However, it also assumes that the Wretched, spirits and creatures of supernatural power represent aspects of God that can be petitioned for help and knowledge.

The major Kellirac holiday is Hultachia, which means “Death Walk.” On this day, all Kellirac prepare for sunset by making as much food as they can, which they will eat some of in a giant meal right before nightfall. The leftovers will be left for the dead. They set candles at the doors and windows, and let the fireplace burn all day. The belief is that at sundown, the borders between this world and the next fall, and any Wanderers who have been deemed worthy will come to visit their loved ones once more before passing into the next world. However, the Wretched will do everything they can to keep the Wanderers from crossing over.

Another major holiday is the Straw Bear Festival, which is a strange development from an Arengish festival that drives out evil. While the specifics of the Arengish traditional festival have been lost, the modern version is a day long festival where a boy who is nearing adulthood dresses in a suit of straw, branches, and greenery. He travels from house to house, howling and dancing. At each home, the woman of the house comes outside with a broom and pantomimes beating the “bear” away. At sundown, the entire town comes out, and all of the village children tear the suit away from the boy within. The suit is burned, and the boy is given gifts, cakes, and small trinkets. This festival is more for the children, who spend the day singing and playing games. Often, groups of children follow the “bear” from house to house, jeering and making fun of the “bear” as he is driven away by the women of the village.

The Kellirac have many ceremonies, but one stands out in importance. After death in battle, the surviving relatives of a slain warrior will place candles at the slain’s bedposts. At sundown, the spirit of the slain warrior is believed to return to rest, and to learn the outcome of the battle. If the slain warrior’s side won, he is released into the next world. If his side lost, he becomes one of The Wanderers. If he died dishonorably, he becomes one of The Wretched.

Once a year like clockwork, an enormous storm, both magical and natural in make, erupts over Eastern Kellirac. It has become a badge of honor to “Ride the Storm,” which means that the warrior in question plants his sword into the ground, and stands in place as the storm buffets him. Most “Storm Riders” do not survive the attempt.

Wow! That’s a lot of description and you inspire me to do more for my own fantasy world. I have also made maps for it when I began writing my short fiction. If interested, stop by http://tiaera.blogspot.com