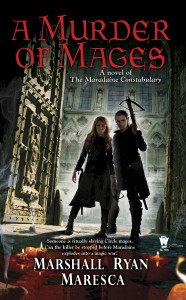

A MURDER OF MAGES releases in eight days! Here’s a preview excerpt to whet your appetite.

A MURDER OF MAGES releases in eight days! Here’s a preview excerpt to whet your appetite.

—-

Satrine Rainey walked to the Inemar Constabulary House carrying a lie. It gnawed at her, every step she took across the bridges to the south side of the city. Taking it across the river would help it pass. The one person who knew the truth was up in North Maradaine, and he almost never crossed the river. The Inemar Constabulary House, on the south bank, might as well have been in another city.

The lie would pass. It was wrapped up in enough truth to pass.

The wind whipped past Satrine, cold and riddled with wet. She pulled her coat tight around her and quickened her pace, overtaking a pedalcart that trundled along one side of the bridge road. The path split on a tiny jut of rock in the middle of the river, the water below choked with sails and barges. Satrine turned onto the Upper Bridge, leading to the neighborhood of Inemar, the heart of the south side of Maradaine.

Satrine hated Inemar. She hated everything south of the river. Not that it mattered. She had to go. And if all went well, she would come back tomorrow, and every day after that.

The steps at the end of the bridge were crowded, people shouting at everyone as they went down to the street level. Dozens of voices selling useless trinkets, witnessing stories of saints, pleading for coins. Two newsboys from competing presses called out lurid stories over each other. Satrine pushed her way through the throng and pressed her way down to the street. She dodged through the traffic of horse carriages and pedalcarts, without missing a step. Muscle memory.

Gray stone dominated Inemar. Gray and tight, this part of the city didn’t waste an inch, buildings pressed up against each other. Not a bit of green in this neighborhood. No trees shading the walkways. Iron grates bordered properties instead of hedges. Even the weeds between the cobblestones were trampled and dead.

“Hey, hey, Waish girl! Waish girl!”

Satrine grimaced. She knew someone was calling her. Most people presumed she was Waish. Here in Maradaine, people forgot that red hair was a common trait in the northern archduchies of Druthal.

“Waish girl! I’m talking to you!” A hand clasped her shoulder.

People had no damn manners in Inemar.

Satrine spun around and swatted away the offending hand. Its owner was a young man with beady eyes and ratlike teeth, wearing a threadbare coat and vest and bearing a disturbingly wide grin.

“Not Waish,” Satrine said. “And not a girl.”

The young man didn’t blink, he just charged on into his spin. “You’re new down here, though, don’t know your way around, just crossed the bridge, am I right? You need yourself a guide and escort, am I right?”

“Not right.” Satrine had already said eight more words than she had planned to say to anyone on the street, and she turned to head back on her way.

“That’s all right, that’s all right.” The young man kept pace with her. “Even if you know your way about, it’s always good for a girl like—lady, I mean—a lady like you to walk with someone, don’t you know. Lot can happen in these streets, you know.”

“I know.”

“So there you have it, miss,” the young man said, crooking his arm through hers as he spoke. “You walk with me and—”

He got no further in his speech. Satrine twisted his arm behind his back, and a moment later she had him on the ground, face pressed into the cobblestone.

“I know where I’m going,” Satrine growled into his ear.

He only grunted in reply. Satrine released him and walked away at full pace, giving only a glance out the corner of her eye to see that the young man was not following her. He had probably slunk back to the bridge to harass another newcomer.

She pushed through the crowd, the usual diverse mix of folks seen in Inemar; most were Druth, with fair skin and brown or blond hair. There was a smattering of greasy-haired Kierans, tanned Acserians, and a handful of other exotic faces, having wandered out of their enclaves in the Little East.

The Constabulary House was only two blocks from the bridge, a small fortress of stone and iron towering over the corner square markets. The building itself had to be ancient. Inemar was full of relics, both buildings and people.

Satrine passed through a gated stone arch where two Constabulary regulars stood at attention, their dark green and red coats crisp and clean in sharp contrast to the gray and rust surroundings.

The regulars just gave her a nod as she passed. And why wouldn’t they? She was a respectable-looking woman, her hair tied back, her face clean. She wore what any decent woman in Maradaine might wear, though her canvas slacks and heavy blouse were hardly what anyone would consider fashionable.

Satrine entered the building itself, into a small lobby, where a wooden counter restricted Satrine from the cramped and crowded Constabulary floor. Desks and benches shoved into every corner, men in Constabulary coats on the benches, behind the desks, pushing through the narrow spaces. Some of the men were Constabulary regulars, some officers.

One woman pressed her way through to the counter. She wore the Constabulary coat, but Satrine noticed a key difference in her uniform. She wore a skirt that stopped just below the knee. It conformed to standards of decency, but it was more like what a schoolgirl should wear rather than a constable.

“Ma’am, can I help you?” The woman’s hair was pulled back tight, which matched the stress in her voice.

“I’m looking for Captain Cinellan?” Satrine asked.

“Second floor,” the woman said, pointing to a narrow corridor to her left. “The inspectors’ offices are up there.” Someone else dropped a pile of papers in front of the woman, and her attention left Satrine immediately.

Satrine went down the corridor, which ended in a tight spiral staircase, solid stone masonry. Satrine went up the steps, running her fingers along the cool wall, her thoughts filled with the paper that felt like it was burning a hole in her coat pocket.

She came out of the stairway to a wide room, bright sunlight streaming through the windows along the eastern wall. The far wall was lined with cabinets and slate boards, and there were desks sparsely placed about the floor, each one with an oil lamp—unlit—hanging above them. Men wearing Constabulary vests worked at the desks while a handful of boys ran through the room. Two boys bolted past Satrine as she came up, racing down the stairs.

A fair-haired woman at the closest desk—the only other woman Satrine saw on the floor—smiled brightly when Satrine approached. “Careful of them.”

“Fast runners,” Satrine said.

“Fastest we have. Did they send you up here with a report?”

“A report?”

“For one of the inspectors?”

“No.” Satrine took a deep breath. This close, the lie was a weight pressing on her chest. “I’m here to see Captain Cinellan.”

“All right,” the woman—Miss Nyla Pyle, based on her brass badge and lack of marriage bracelet—said. “Can I have your name?”

“Rainey. Satrine Rainey.”

Miss Pyle’s eyes flashed with recognition. She gave a small nod as she bit at her bottom lip. “This way, all right?”

The woman led Satrine through the inspectors’ work floor, past various men discussing the cases they were working on. Satrine only caught snippets of conversation before reaching the door with a brass plaque on it: captain brace cinellan.

The woman guiding Satrine knocked and opened the door simultaneously. Captain Cinellan’s office was dim, no windows, only burning oil lamps and candles on his desk. The man himself was hunched over the desk, the muscular frame of an old soldier, beat down and bent with age. Not that he was that old; his face had few lines and his hair untouched by gray. But he held himself like an old man. A tired man.

“Yes, Miss Pyle?” he asked.

“Missus Satrine Rainey to see you, Captain,” Miss Pyle said, putting a strong emphasis on Satrine’s last name. Captain Cinellan’s weary eyes glanced over to Satrine, and they sparked with sympathy.

“Yes, of course,” he said. He got up from the desk and crossed over to Satrine, extending his hand. “Missus Rainey, very good to meet you.”

Satrine took his hand and shook it, giving him a strong, solid grip. She wasn’t going to give him anything less, give him any cause to doubt her resolve.

Cinellan gestured to her to take the chair on the other side of his desk, despite it being full of books and ledgers. Miss Pyle grabbed them off the chair before anyone else spoke.

“Return these to the archives, Captain?”

“Yes, Miss Pyle. And, um . . . tea with—”

“Honey and cream,” Miss Pyle finished. “Anything for you, Missus Rainey?”

“Tea, yes,” Satrine said. “Cream only.”

Miss Pyle nodded and left the office as gracefully as possible with her arms full, deftly shutting the door with a swing of her foot.

Captain Cinellan sat down behind his desk. “So, Missus Rainey, let me just say . . . when we all heard about what happened to your husband, well . . . most of us didn’t know him down here on the south bank, of course, except by reputation. And when something . . .” He faltered, biting at his lip.

“Devastating occurs?” Satrine offered. That was the best word to describe what had happened to Loren.

Cinellan nodded. “Absolutely. It gives a man pause. Especially for all of us here in the Green and Red.”

“What happened to my husband was—is—tragic, Captain Cinellan, but I have to . . .”

“Yes, I know,” Captain Cinellan said. He dug through the papers on his desk. “I received word from Commissioner Enbrain that you would be coming here.”

Satrine’s heart jumped to her throat. If Enbrain had sent a letter here as well, then that would ruin everything. She couldn’t have that. Loren needed her to succeed. The girls needed it.

“He sent you my orders?”

“Orders, what?” Cinellan looked confused. “No, he just sent a runner with word you were going to be coming in here today.”

“So you don’t have the orders?” This was the moment. She forced the words out despite the rising bile in her throat. “You’re to give me a position here.” She pulled the letter out of her pocket.

Cinellan glanced at the letter, waxed shut with Commissioner Enbrain’s seal. Or, more correctly, an excellent forgery that Satrine had spent hours copying. Cinellan gave it no more than two seconds of regard before cracking it open and reading the letter.

“I’m to make you what?”

Satrine almost answered, but she bit her tongue before she revealed that she knew the contents of the sealed letter.

“This can’t be serious!”

“What is it?”

“According to this, I’m to make you an inspector.”

Inspector Third Class, to be precise. Satrine dared well enough putting that on the letter.

She had worked her expression in the mirror for an hour. Old skills, long unpracticed, but still in her muscles. She needed to convey just the right degree of pleasant surprise without approaching shock. She opened her eyes wide and drew her breath in sharply. She put her hand over her chest, as if her heart was racing, and asked, “And what would the salary be?”

“Salary!” Cinellan snapped. “Missus Rainey, do you have any experience related to investigative work?”

“Beyond having a husband who was an Inspector First Class?”

“That is not a qualification, Missus Rainey. My wife plays the flute excellently, yet I’m only thumbs.”

“Fair enough,” Satrine knew that wasn’t going to keep this wagon rolling. “Prior to my marriage, I was an agent in Druth Intelligence.”

Cinellan raised his eyebrow. “For how long?”

Satrine knew she had intrigued him, at least enough that he could be reeled in. “Four years.” She held her breath for a moment, letting a small smile form. “Officially.”

“I don’t suppose that’s verifiable.”

Satrine knew that was coming. “We don’t get tattoos like army or navy does.”

“You understand I can’t just take your word . . .”

“Of course,” Satrine said, pulling another letter from her pocket, this one completely legitimate. “I know it isn’t exactly—”

He gave it a quick glance. “I’ve seen enough ‘thanks for service to the Crown’ letters to know what they really mean.” Cinellan grunted in something sounding like disapproval. “Most inspectors have several years walking the streets first.”

“Do you need my whole history, Captain?”

“I need some reason why I should make inspector some—no disrespect to you, Missus Rainey—some random woman who walks off the street over the heads of several men who’ve earned the posting!”

Satrine had been expecting this. Her forgery, as impeccable as it might be, wouldn’t be enough to convince any captain worth the crowns he was paid to take her on.

“Leaving aside that I am not some ‘random woman,’ but the wife of a dedicated constable—a man who all but died for this city—I do have the skills and training necessary to serve as an inspector.”

“I’ll grant four years in Intelligence is nothing to scoff at. Even still, no formal training is a substitute for knowing these streets.”

“Streets of Inemar?” Satrine asked. She didn’t bother to hide her grin. “I grew up not three blocks from here.”

Cinellan chuckled. “You can’t try and trick me with that. You’re a North Maradaine lady if ever I met one.”

“Oy, that what you think?” Satrine slipped into her old accent like it was a comfortable shoe. “No surprise sticks like you never clipped any of us.”

Cinellan’s eyebrow went up. “What corner?”

“Jent and Tannen.”

“No chance! When I first got my coat, I knew every rat and bird in that part of the neighborhood. The only Waishen-haired girl back in the day was—”

“Trini ‘Tricky.’”

“Exactly! And she . . . she . . .” His eyes went wide. “Impossible!”

Satrine bowed her head gracefully. “It was another life.”

“I know for a fact that there is a report down in the archives on the investigation of her . . . disappearance.”

Satrine shrugged. “My recruitment into Druth Intelligence was . . . unorthodox. I didn’t have a chance to tell anyone I was going.”

Cinellan laughed out loud. He was warming to her. That was always her gift—to survive on the street, to thrive in Intelligence, she made people fond of her. She used to wrap herself in lies on a daily basis, but to sell one to a man like her husband, a man just doing his job honestly, it made her ill.

“I’m intrigued, Missus Rainey, and the commissioner notes that we should be giving more positions in the Constabulary force to women.” He shook the letter casually. The commissioner had written that very point, but as an argument to make Satrine a clerk. A position that paid five crowns a week. That salary would put her family on the street; she would never let that happen to her daughters. Her girls would never have to do what she lived through.

Miss Pyle came back in with a tea tray. Cinellan dropped his light demeanor while Miss Pyle was there, thanked her for the tea, and waited for her to leave before sipping it. He sat at his desk, teacup in hand, for some time in silence. Satrine picked up her own, but didn’t drink any, not yet. She didn’t think it would be particularly good, anyway.

“I’ll be frank, Captain,” Satrine said. “I’m not a widow, though I may as well be. I have two daughters whom I am putting through school, a husband who needs caring for, rent, city taxes, and several other expenses. If I’m not bringing home twenty crowns a week, then it all falls apart.”

“Standard pay for Inspector Third Class is nineteen crowns five.”

“I can start with that.” There was enough saved up—especially with what the boys at Loren’s district house gave when they scraped together—to last on nineteen-five for a few months. Come the summer, she would find some way to earn those last fifteen ticks.

“Ambitious, good,” he said. “Still doesn’t sit right, even with the commissioner pushing it.”

“I’d be happy to be put to the test.”

“Hmmph,” Cinellan snorted. “What sort of test?”

“Give me a week,” she said. “Any floor sergeants grouse, you tell them you got pushed by the commissioner.”

Cinellan tapped the letter on his desk. “Which I have.”

“If you don’t think I measure up at the end of the week, you send me on my way. You can tell the commissioner you tried and it didn’t work.”

Satrine’s heart pounded like a hammer, threatening to smash through her chest.

“Fine,” Cinellan said. “Though I got to tell you, it’s mostly so I can pull your old file from the archives and write in it that I solved a twenty-year-old case.”

“Thank you, Captain,” Satrine said. Most of the tension in her shoulders relaxed. Not all, not until she had the job secure. She took a drink of her tea. It was, as she had predicted, awful.

“Don’t thank me yet,” he said. “You haven’t met your partner.”

One comment

Comments are closed.